/ Design Patterns / Behavioral Patterns

Intent

State is a behavioral design pattern that lets an object alter its behavior when its internal state changes. It appears as if the object changed its class.

Problem

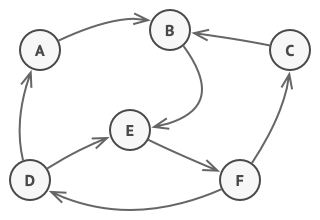

The State pattern is closely related to the concept of a Finite-State Machine.

Finite-State Machine.

The main idea is that, at any given moment, there’s a finite number of states which a program can be in. Within any unique state, the program behaves differently, and the program can be switched from one state to another instantaneously. However, depending on a current state, the program may or may not switch to certain other states. These switching rules, called transitions, are also finite and predetermined.

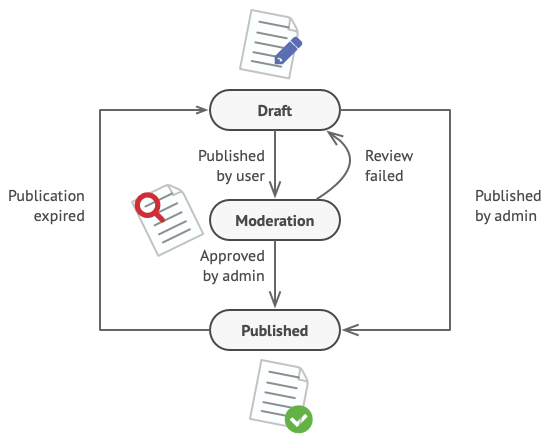

You can also apply this approach to objects. Imagine that we have a Document class. A document can be in one of three states: Draft, Moderation and Published. The publish method of the document works a little bit differently in each state:

- In

Draft, it moves the document to moderation. - In

Moderation, it makes the document public, but only if the current user is an administrator. - In

Published, it doesn’t do anything at all.

Possible states and transitions of a document object.

State machines are usually implemented with lots of conditional operators (if or switch) that select the appropriate behavior depending on the current state of the object. Usually, this “state” is just a set of values of the object’s fields. Even if you’ve never heard about finite-state machines before, you’ve probably implemented a state at least once. Does the following code structure ring a bell?

class Document is

field state: string

// ...

method publish() is

switch (state)

"draft":

state = "moderation"

break

"moderation":

if (currentUser.role == 'admin')

state = "published"

break

"published":

// Do nothing.

break

// ...

The biggest weakness of a state machine based on conditionals reveals itself once we start adding more and more states and state-dependent behaviors to the Document class. Most methods will contain monstrous conditionals that pick the proper behavior of a method according to the current state. Code like this is very difficult to maintain because any change to the transition logic may require changing state conditionals in every method.

The problem tends to get bigger as a project evolves. It’s quite difficult to predict all possible states and transitions at the design stage. Hence, a lean state machine built with a limited set of conditionals can grow into a bloated mess over time.

Solution

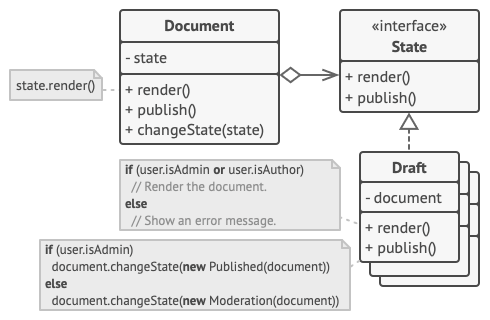

The State pattern suggests that you create new classes for all possible states of an object and extract all state-specific behaviors into these classes.

Instead of implementing all behaviors on its own, the original object, called context, stores a reference to one of the state objects that represents its current state, and delegates all the state-related work to that object.

Document delegates the work to a state object.

To transition the context into another state, replace the active state object with another object that represents that new state. This is possible only if all state classes follow the same interface and the context itself works with these objects through that interface.

This structure may look similar to the Strategy pattern, but there’s one key difference. In the State pattern, the particular states may be aware of each other and initiate transitions from one state to another, whereas strategies almost never know about each other.

Real-World Analogy

The buttons and switches in your smartphone behave differently depending on the current state of the device:

- When the phone is unlocked, pressing buttons leads to executing various functions.

- When the phone is locked, pressing any button leads to the unlock screen.

- When the phone’s charge is low, pressing any button shows the charging screen.

Structure

-

Context stores a reference to one of the concrete state objects and delegates to it all state-specific work. The context communicates with the state object via the state interface. The context exposes a setter for passing it a new state object.

-

The State interface declares the state-specific methods. These methods should make sense for all concrete states because you don’t want some of your states to have useless methods that will never be called.

-

Concrete States provide their own implementations for the state-specific methods. To avoid duplication of similar code across multiple states, you may provide intermediate abstract classes that encapsulate some common behavior.

State objects may store a backreference to the context object. Through this reference, the state can fetch any required info from the context object, as well as initiate state transitions.

-

Both context and concrete states can set the next state of the context and perform the actual state transition by replacing the state object linked to the context.

Pseudocode

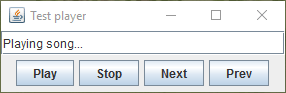

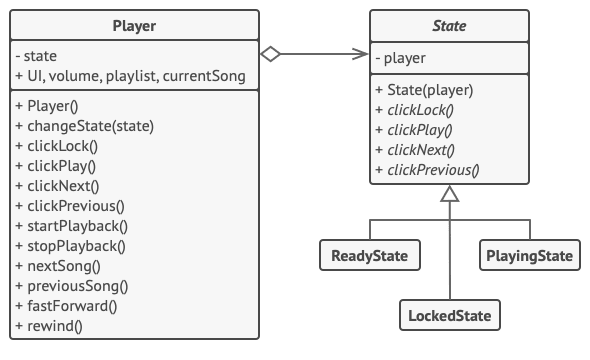

In this example, the State pattern lets the same controls of the media player behave differently, depending on the current playback state.

Example of changing object behavior with state objects.

The main object of the player is always linked to a state object that performs most of the work for the player. Some actions replace the current state object of the player with another, which changes the way the player reacts to user interactions.

// The AudioPlayer class acts as a context. It also maintains a

// reference to an instance of one of the state classes that

// represents the current state of the audio player.

class AudioPlayer is

field state: State

field UI, volume, playlist, currentSong

constructor AudioPlayer() is

this.state = new ReadyState(this)

// Context delegates handling user input to a state

// object. Naturally, the outcome depends on what state

// is currently active, since each state can handle the

// input differently.

UI = new UserInterface()

UI.lockButton.onClick(this.clickLock)

UI.playButton.onClick(this.clickPlay)

UI.nextButton.onClick(this.clickNext)

UI.prevButton.onClick(this.clickPrevious)

// Other objects must be able to switch the audio player's

// active state.

method changeState(state: State) is

this.state = state

// UI methods delegate execution to the active state.

method clickLock() is

state.clickLock()

method clickPlay() is

state.clickPlay()

method clickNext() is

state.clickNext()

method clickPrevious() is

state.clickPrevious()

// A state may call some service methods on the context.

method startPlayback() is

// ...

method stopPlayback() is

// ...

method nextSong() is

// ...

method previousSong() is

// ...

method fastForward(time) is

// ...

method rewind(time) is

// ...

// The base state class declares methods that all concrete

// states should implement and also provides a backreference to

// the context object associated with the state. States can use

// the backreference to transition the context to another state.

abstract class State is

protected field player: AudioPlayer

// Context passes itself through the state constructor. This

// may help a state fetch some useful context data if it's

// needed.

constructor State(player) is

this.player = player

abstract method clickLock()

abstract method clickPlay()

abstract method clickNext()

abstract method clickPrevious()

// Concrete states implement various behaviors associated with a

// state of the context.

class LockedState extends State is

// When you unlock a locked player, it may assume one of two

// states.

method clickLock() is

if (player.playing)

player.changeState(new PlayingState(player))

else

player.changeState(new ReadyState(player))

method clickPlay() is

// Locked, so do nothing.

method clickNext() is

// Locked, so do nothing.

method clickPrevious() is

// Locked, so do nothing.

// They can also trigger state transitions in the context.

class ReadyState extends State is

method clickLock() is

player.changeState(new LockedState(player))

method clickPlay() is

player.startPlayback()

player.changeState(new PlayingState(player))

method clickNext() is

player.nextSong()

method clickPrevious() is

player.previousSong()

class PlayingState extends State is

method clickLock() is

player.changeState(new LockedState(player))

method clickPlay() is

player.stopPlayback()

player.changeState(new ReadyState(player))

method clickNext() is

if (event.doubleclick)

player.nextSong()

else

player.fastForward(5)

method clickPrevious() is

if (event.doubleclick)

player.previous()

else

player.rewind(5)

Applicability

Use the State pattern when you have an object that behaves differently depending on its current state, the number of states is enormous, and the state-specific code changes frequently.

The pattern suggests that you extract all state-specific code into a set of distinct classes. As a result, you can add new states or change existing ones independently of each other, reducing the maintenance cost.

Use the pattern when you have a class polluted with massive conditionals that alter how the class behaves according to the current values of the class’s fields.

The State pattern lets you extract branches of these conditionals into methods of corresponding state classes. While doing so, you can also clean temporary fields and helper methods involved in state-specific code out of your main class.

Use State when you have a lot of duplicate code across similar states and transitions of a condition-based state machine.

The State pattern lets you compose hierarchies of state classes and reduce duplication by extracting common code into abstract base classes.

How to Implement

-

Decide what class will act as the context. It could be an existing class which already has the state-dependent code; or a new class, if the state-specific code is distributed across multiple classes.

-

Declare the state interface. Although it may mirror all the methods declared in the context, aim only for those that may contain state-specific behavior.

-

For every actual state, create a class that derives from the state interface. Then go over the methods of the context and extract all code related to that state into your newly created class.

While moving the code to the state class, you might discover that it depends on private members of the context. There are several workarounds:

- Make these fields or methods public.

- Turn the behavior you’re extracting into a public method in the context and call it from the state class. This way is ugly but quick, and you can always fix it later.

- Nest the state classes into the context class, but only if your programming language supports nesting classes.

-

In the context class, add a reference field of the state interface type and a public setter that allows overriding the value of that field.

-

Go over the method of the context again and replace empty state conditionals with calls to corresponding methods of the state object.

-

To switch the state of the context, create an instance of one of the state classes and pass it to the context. You can do this within the context itself, or in various states, or in the client. Wherever this is done, the class becomes dependent on the concrete state class that it instantiates.

Pros and Cons

- Single Responsibility Principle. Organize the code related to particular states into separate classes.

- Open/Closed Principle. Introduce new states without changing existing state classes or the context.

-

Simplify the code of the context by eliminating bulky state machine conditionals.

- Applying the pattern can be overkill if a state machine has only a few states or rarely changes.

Relations with Other Patterns

-

Bridge, State, Strategy (and to some degree Adapter) have very similar structures. Indeed, all of these patterns are based on composition, which is delegating work to other objects. However, they all solve different problems. A pattern isn’t just a recipe for structuring your code in a specific way. It can also communicate to other developers the problem the pattern solves.

-

State can be considered as an extension of Strategy. Both patterns are based on composition: they change the behavior of the context by delegating some work to helper objects. Strategy makes these objects completely independent and unaware of each other. However, State doesn’t restrict dependencies between concrete states, letting them alter the state of the context at will.

Code Example

State is a behavioral design pattern that allows an object to change the behavior when its internal state changes.

The pattern extracts state-related behaviors into separate state classes and forces the original object to delegate the work to an instance of these classes, instead of acting on its own.

Usage of the pattern in Java

Complexity:

Popularity:

Usage examples: The State pattern is commonly used in Java to convert massive switch-base state machines into the objects.

Here are some examples of the State pattern in core Java libraries:

javax.faces.lifecycle.LifeCycle#execute()(controlled by theFacesServlet: behaviour is dependent on current phase (state) of JSF lifecycle)

Identification: State pattern can be recognized by methods that change their behavior depending on the objects’ state, controlled externally.

Interface of a media player

In this example, the State pattern lets the same media player controls behave differently, depending on the current playback state. The main class of the player contains a reference to a state object, which performs most of the work for the player. Some actions may end-up replacing the state object with another, which changes the way the player reacts to the user interactions.

states

states/State.java: Common state interface

package algamza.state.example.states;

import algamza.state.example.ui.Player;

/**

* Common interface for all states.

*/

public abstract class State {

Player player;

/**

* Context passes itself through the state constructor. This may help a

* state to fetch some useful context data if needed.

*/

State(Player player) {

this.player = player;

}

public abstract String onLock();

public abstract String onPlay();

public abstract String onNext();

public abstract String onPrevious();

}

states/LockedState.java

package algamza.state.example.states;

import algamza.state.example.ui.Player;

/**

* Concrete states provide the special implementation for all interface methods.

*/

public class LockedState extends State {

LockedState(Player player) {

super(player);

player.setPlaying(false);

}

@Override

public String onLock() {

if (player.isPlaying()) {

player.changeState(new ReadyState(player));

return "Stop playing";

} else {

return "Locked...";

}

}

@Override

public String onPlay() {

player.changeState(new ReadyState(player));

return "Ready";

}

@Override

public String onNext() {

return "Locked...";

}

@Override

public String onPrevious() {

return "Locked...";

}

}

states/ReadyState.java

package algamza.state.example.states;

import algamza.state.example.ui.Player;

/**

* They can also trigger state transitions in the context.

*/

public class ReadyState extends State {

public ReadyState(Player player) {

super(player);

}

@Override

public String onLock() {

player.changeState(new LockedState(player));

return "Locked...";

}

@Override

public String onPlay() {

String action = player.startPlayback();

player.changeState(new PlayingState(player));

return action;

}

@Override

public String onNext() {

return "Locked...";

}

@Override

public String onPrevious() {

return "Locked...";

}

}

states/PlayingState.java

package algamza.state.example.states;

import algamza.state.example.ui.Player;

public class PlayingState extends State {

PlayingState(Player player) {

super(player);

}

@Override

public String onLock() {

player.changeState(new LockedState(player));

player.setCurrentTrackAfterStop();

return "Stop playing";

}

@Override

public String onPlay() {

player.changeState(new ReadyState(player));

return "Paused...";

}

@Override

public String onNext() {

return player.nextTrack();

}

@Override

public String onPrevious() {

return player.previousTrack();

}

}

ui

ui/Player.java: Player primary code

package algamza.state.example.ui;

import algamza.state.example.states.ReadyState;

import algamza.state.example.states.State;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class Player {

private State state;

private boolean playing = false;

private List<String> playlist = new ArrayList<>();

private int currentTrack = 0;

public Player() {

this.state = new ReadyState(this);

setPlaying(true);

for (int i = 1; i <= 12; i++) {

playlist.add("Track " + i);

}

}

public void changeState(State state) {

this.state = state;

}

public State getState() {

return state;

}

public void setPlaying(boolean playing) {

this.playing = playing;

}

public boolean isPlaying() {

return playing;

}

public String startPlayback() {

return "Playing " + playlist.get(currentTrack);

}

public String nextTrack() {

currentTrack++;

if (currentTrack > playlist.size() - 1) {

currentTrack = 0;

}

return "Playing " + playlist.get(currentTrack);

}

public String previousTrack() {

currentTrack--;

if (currentTrack < 0) {

currentTrack = playlist.size() - 1;

}

return "Playing " + playlist.get(currentTrack);

}

public void setCurrentTrackAfterStop() {

this.currentTrack = 0;

}

}

ui/UI.java: Player’s GUI

package algamza.state.example.ui;

import javax.swing.*;

import java.awt.*;

public class UI {

private Player player;

private static JTextField textField = new JTextField();

public UI(Player player) {

this.player = player;

}

public void init() {

JFrame frame = new JFrame("Test player");

frame.setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE);

JPanel context = new JPanel();

context.setLayout(new BoxLayout(context, BoxLayout.Y_AXIS));

frame.getContentPane().add(context);

JPanel buttons = new JPanel(new FlowLayout(FlowLayout.CENTER));

context.add(textField);

context.add(buttons);

// Context delegates handling user's input to a state object. Naturally,

// the outcome will depend on what state is currently active, since all

// states can handle the input differently.

JButton play = new JButton("Play");

play.addActionListener(e -> textField.setText(player.getState().onPlay()));

JButton stop = new JButton("Stop");

stop.addActionListener(e -> textField.setText(player.getState().onLock()));

JButton next = new JButton("Next");

next.addActionListener(e -> textField.setText(player.getState().onNext()));

JButton prev = new JButton("Prev");

prev.addActionListener(e -> textField.setText(player.getState().onPrevious()));

frame.setVisible(true);

frame.setSize(300, 100);

buttons.add(play);

buttons.add(stop);

buttons.add(next);

buttons.add(prev);

}

}

Demo.java: Initialization code

package algamza.state.example;

import algamza.state.example.ui.Player;

import algamza.state.example.ui.UI;

/**

* Demo class. Everything comes together here.

*/

public class Demo {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Player player = new Player();

UI ui = new UI(player);

ui.init();

}

}

OutputDemo.png: Screenshot