/ Design Patterns / Behavioral Patterns

Intent

Visitor is a behavioral design pattern that lets you separate algorithms from the objects on which they operate.

Problem

Imagine that your team develops an app which works with geographic information structured as one colossal graph. Each node of the graph may represent a complex entity such as a city, but also more granular things like industries, sightseeing areas, etc. The nodes are connected with others if there’s a road between the real objects that they represent. Under the hood, each node type is represented by its own class, while each specific node is an object.

Exporting the graph into XML.

At some point, you got a task to implement exporting the graph into XML format. At first, the job seemed pretty straightforward. You planned to add an export method to each node class and then leverage recursion to go over each node of the graph, executing the export method. The solution was simple and elegant: thanks to polymorphism, you weren’t coupling the code which called the export method to concrete classes of nodes.

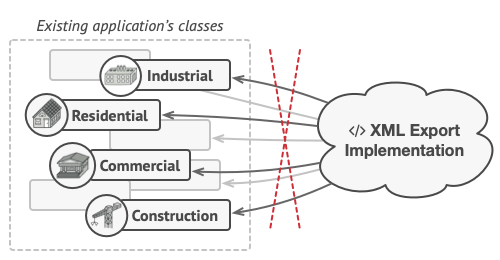

Unfortunately, the system architect refused to allow you to alter existing node classes. He said that the code was already in production and he didn’t want to risk breaking it because of a potential bug in your changes.

The XML export method had to be added into all node classes, which bore the risk of breaking the whole application if any bugs slipped through along with the change.

Besides, he questioned whether it makes sense to have the XML export code within the node classes. The primary job of these classes was to work with geodata. The XML export behavior would look alien there.

There was another reason for the refusal. It was highly likely that after this feature was implemented, someone from the marketing department would ask you to provide the ability to export into a different format, or request some other weird stuff. This would force you to change those precious and fragile classes again.

Solution

The Visitor pattern suggests that you place the new behavior into a separate class called visitor, instead of trying to integrate it into existing classes. The original object that had to perform the behavior is now passed to one of the visitor’s methods as an argument, providing the method access to all necessary data contained within the object.

Now, what if that behavior can be executed over objects of different classes? For example, in our case with XML export, the actual implementation will probably be a little bit different across various node classes. Thus, the visitor class may define not one, but a set of methods, each of which could take arguments of different types, like this:

class ExportVisitor implements Visitor is

method doForCity(City c) { ... }

method doForIndustry(Industry f) { ... }

method doForSightSeeing(SightSeeing ss) { ... }

// ...

But how exactly would we call these methods, especially when dealing with the whole graph? These methods have different signatures, so we can’t use polymorphism. To pick a proper visitor method that’s able to process a given object, we’d need to check its class. Doesn’t this sound like a nightmare?

foreach (Node node in graph)

if (node instanceof City)

exportVisitor.doForCity((City) node)

if (node instanceof Industry)

exportVisitor.doForIndustry((Industry) node)

// ...

}

You might ask, why don’t we use method overloading? That’s when you give all methods the same name, even if they support different sets of parameters. Unfortunately, even assuming that our programming language supports it at all (as Java and C# do), it won’t help us. Since the exact class of a node object is unknown in advance, the overloading mechanism won’t be able to determine the correct method to execute. It’ll default to the method that takes an object of the base Node class.

However, the Visitor pattern addresses this problem. It uses a technique called Double Dispatch, which helps to execute the proper method on an object without cumbersome conditionals. Instead of letting the client select a proper version of the method to call, how about we delegate this choice to objects we’re passing to the visitor as an argument? Since the objects know their own classes, they’ll be able to pick a proper method on the visitor less awkwardly. They “accept” a visitor and tell it what visiting method should be executed.

// Client code

foreach (Node node in graph)

node.accept(exportVisitor)

// City

class City is

method accept(Visitor v) is

v.doForCity(this)

// ...

// Industry

class Industry is

method accept(Visitor v) is

v.doForIndustry(this)

// ...

I confess. We had to change the node classes after all. But at least the change is trivial and it lets us add further behaviors without altering the code once again.

Now, if we extract a common interface for all visitors, all existing nodes can work with any visitor you introduce into the app. If you find yourself introducing a new behavior related to nodes, all you have to do is implement a new visitor class.

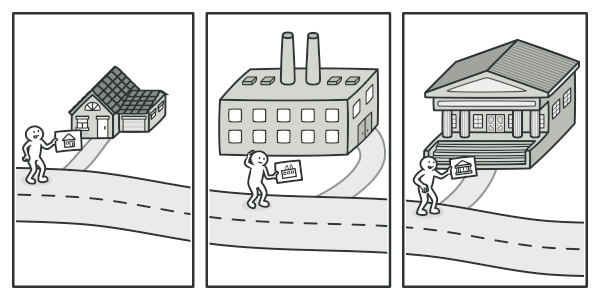

Real-World Analogy

A good insurance agent is always ready to offer different policies to various types of organizations.

Imagine a seasoned insurance agent who’s eager to get new customers. He can visit every building in a neighborhood, trying to sell insurance to everyone he meets. Depending on the type of organization that occupies the building, he can offer specialized insurance policies:

- If it’s a residential building, he sells medical insurance.

- If it’s a bank, he sells theft insurance.

- If it’s a coffee shop, he sells fire and flood insurance.

Structure

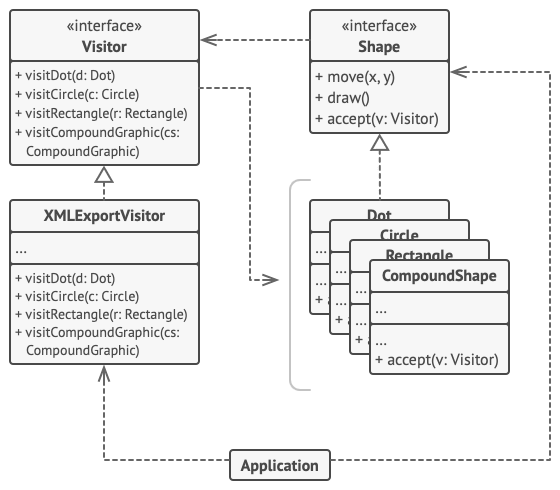

-

The Visitor interface declares a set of visiting methods that can take concrete elements of an object structure as arguments. These methods may have the same names if the program is written in a language that supports overloading, but the type of their parameters must be different.

-

Each Concrete Visitor implements several versions of the same behaviors, tailored for different concrete element classes.

-

The Element interface declares a method for “accepting” visitors. This method should have one parameter declared with the type of the visitor interface.

-

Each Concrete Element must implement the acceptance method. The purpose of this method is to redirect the call to the proper visitor’s method corresponding to the current element class. Be aware that even if a base element class implements this method, all subclasses must still override this method in their own classes and call the appropriate method on the visitor object.

-

The Client usually represents a collection or some other complex object (for example, a Composite tree). Usually, clients aren’t aware of all the concrete element classes because they work with objects from that collection via some abstract interface.

Pseudocode

In this example, the Visitor pattern adds XML export support to the class hierarchy of geometric shapes.

Exporting various types of objects into XML format via a visitor object.

// The element interface declares an `accept` method that takes

// the base visitor interface as an argument.

interface Shape is

method move(x, y)

method draw()

method accept(v: Visitor)

// Each concrete element class must implement the `accept`

// method in such a way that it calls the visitor's method that

// corresponds to the element's class.

class Dot extends Shape is

// ...

// Note that we're calling `visitDot`, which matches the

// current class name. This way we let the visitor know the

// class of the element it works with.

method accept(v: Visitor) is

v.visitDot(this)

class Circle extends Dot is

// ...

method accept(v: Visitor) is

v.visitCircle(this)

class Rectangle extends Shape is

// ...

method accept(v: Visitor) is

v.visitRectangle(this)

class CompoundShape implements Shape is

// ...

method accept(v: Visitor) is

v.visitCompoundShape(this)

// The Visitor interface declares a set of visiting methods that

// correspond to element classes. The signature of a visiting

// method lets the visitor identify the exact class of the

// element that it's dealing with.

interface Visitor is

method visitDot(d: Dot)

method visitCircle(c: Circle)

method visitRectangle(r: Rectangle)

method visitCompoundShape(cs: CompoundShape)

// Concrete visitors implement several versions of the same

// algorithm, which can work with all concrete element classes.

//

// You can experience the biggest benefit of the Visitor pattern

// when using it with a complex object structure such as a

// Composite tree. In this case, it might be helpful to store

// some intermediate state of the algorithm while executing the

// visitor's methods over various objects of the structure.

class XMLExportVisitor implements Visitor is

method visitDot(d: Dot) is

// Export the dot's ID and center coordinates.

method visitCircle(c: Circle) is

// Export the circle's ID, center coordinates and

// radius.

method visitRectangle(r: Rectangle) is

// Export the rectangle's ID, left-top coordinates,

// width and height.

method visitCompoundShape(cs: CompoundShape) is

// Export the shape's ID as well as the list of its

// children's IDs.

// The client code can run visitor operations over any set of

// elements without figuring out their concrete classes. The

// accept operation directs a call to the appropriate operation

// in the visitor object.

class Application is

field allShapes: array of Shapes

method export() is

exportVisitor = new XMLExportVisitor()

foreach (shape in allShapes) do

shape.accept(exportVisitor)

If you wonder why we need the accept method in this example, my article Visitor and Double Dispatch addresses this question in detail.

Applicability

Use the Visitor when you need to perform an operation on all elements of a complex object structure (for example, an object tree).

The Visitor pattern lets you execute an operation over a set of objects with different classes by having a visitor object implement several variants of the same operation, which correspond to all target classes.

Use the Visitor to clean up the business logic of auxiliary behaviors.

The pattern lets you make the primary classes of your app more focused on their main jobs by extracting all other behaviors into a set of visitor classes.

Use the pattern when a behavior makes sense only in some classes of a class hierarchy, but not in others.

You can extract this behavior into a separate visitor class and implement only those visiting methods that accept objects of relevant classes, leaving the rest empty.

How to Implement

-

Declare the visitor interface with a set of “visiting” methods, one per each concrete element class that exists in the program.

-

Declare the element interface. If you’re working with an existing element class hierarchy, add the abstract “acceptance” method to the base class of the hierarchy. This method should accept a visitor object as an argument.

-

Implement the acceptance methods in all concrete element classes. These methods must simply redirect the call to a visiting method on the incoming visitor object which matches the class of the current element.

-

The element classes should only work with visitors via the visitor interface. Visitors, however, must be aware of all concrete element classes, referenced as parameter types of the visiting methods.

-

For each behavior that can’t be implemented inside the element hierarchy, create a new concrete visitor class and implement all of the visiting methods.

You might encounter a situation where the visitor will need access to some private members of the element class. In this case, you can either make these fields or methods public, violating the element’s encapsulation, or nest the visitor class in the element class. The latter is only possible if you’re lucky to work with a programming language that supports nested classes.

-

The client must create visitor objects and pass them into elements via “acceptance” methods.

Pros and Cons

- Open/Closed Principle. You can introduce a new behavior that can work with objects of different classes without changing these classes.

- Single Responsibility Principle. You can move multiple versions of the same behavior into the same class.

-

A visitor object can accumulate some useful information while working with various objects. This might be handy when you want to traverse some complex object structure, such as an object tree, and apply the visitor to each object of this structure.

- You need to update all visitors each time a class gets added to or removed from the element hierarchy.

- Visitors might lack the necessary access to the private fields and methods of the elements that they’re supposed to work with.

Relations with Other Patterns

-

You can treat Visitor as a powerful version of the Command pattern. Its objects can execute operations over various objects of different classes.

-

You can use Visitor to execute an operation over an entire Composite tree.

-

You can use Visitor along with Iterator to traverse a complex data structure and execute some operation over its elements, even if they all have different classes.

Code Example

Visitor is a behavioral design pattern that allows adding new behaviors to existing class hierarchy without altering any existing code.

Read why Visitors can’t be simply replaced with method overloading in our article Visitor and Double Dispatch.

Usage of the pattern in Java

Complexity:

Popularity:

Usage examples: Visitor isn’t a very common pattern because of its complexity and narrow applicability.

Here are some examples of pattern in code Java libraries:

javax.lang.model.element.AnnotationValueandAnnotationValueVisitorjavax.lang.model.element.ElementandElementVisitorjavax.lang.model.type.TypeMirrorandTypeVisitorjava.nio.file.FileVisitorandSimpleFileVisitorjavax.faces.component.visit.VisitContextandVisitCallback

Exporting shapes into XML

In this example, we would want to export a set of geometric shapes into XML. The catch is that we don’t want to change the code of shapes directly or at least keep it to the minimum.

In the end, the Visitor pattern establishes an infrastructure that allows us to add any behaviors to the shapes hierarchy without changing the existing code of those classes.

shapes

shapes/Shape.java: Common shape interface

package algamza.visitor.example.shapes;

import algamza.visitor.example.visitor.Visitor;

public interface Shape {

void move(int x, int y);

void draw();

String accept(Visitor visitor);

}

shapes/Dot.java: A dot

package algamza.visitor.example.shapes;

import algamza.visitor.example.visitor.Visitor;

public class Dot implements Shape {

private int id;

private int x;

private int y;

public Dot() {

}

public Dot(int id, int x, int y) {

this.id = id;

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

@Override

public void move(int x, int y) {

// move shape

}

@Override

public void draw() {

// draw shape

}

public String accept(Visitor visitor) {

return visitor.visitDot(this);

}

public int getX() {

return x;

}

public int getY() {

return y;

}

public int getId() {

return id;

}

}

shapes/Circle.java: A circle

package algamza.visitor.example.shapes;

import algamza.visitor.example.visitor.Visitor;

public class Circle extends Dot {

private int radius;

public Circle(int id, int x, int y, int radius) {

super(id, x, y);

this.radius = radius;

}

@Override

public String accept(Visitor visitor) {

return visitor.visitCircle(this);

}

public int getRadius() {

return radius;

}

}

shapes/Rectangle.java: A rectangle

package algamza.visitor.example.shapes;

import algamza.visitor.example.visitor.Visitor;

public class Rectangle implements Shape {

private int id;

private int x;

private int y;

private int width;

private int height;

public Rectangle(int id, int x, int y, int width, int height) {

this.id = id;

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

this.width = width;

this.height = height;

}

@Override

public String accept(Visitor visitor) {

return visitor.visitRectangle(this);

}

@Override

public void move(int x, int y) {

// move shape

}

@Override

public void draw() {

// draw shape

}

public int getId() {

return id;

}

public int getX() {

return x;

}

public int getY() {

return y;

}

public int getWidth() {

return width;

}

public int getHeight() {

return height;

}

}

shapes/CompoundShape.java: A compound shape

package algamza.visitor.example.shapes;

import algamza.visitor.example.visitor.Visitor;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class CompoundShape implements Shape {

public int id;

public List<Shape> children = new ArrayList<>();

public CompoundShape(int id) {

this.id = id;

}

@Override

public void move(int x, int y) {

// move shape

}

@Override

public void draw() {

// draw shape

}

public int getId() {

return id;

}

@Override

public String accept(Visitor visitor) {

return visitor.visitCompoundGraphic(this);

}

public void add(Shape shape) {

children.add(shape);

}

}

visitor

visitor/Visitor.java: Common visitor interface

package algamza.visitor.example.visitor;

import algamza.visitor.example.shapes.Circle;

import algamza.visitor.example.shapes.CompoundShape;

import algamza.visitor.example.shapes.Dot;

import algamza.visitor.example.shapes.Rectangle;

public interface Visitor {

String visitDot(Dot dot);

String visitCircle(Circle circle);

String visitRectangle(Rectangle rectangle);

String visitCompoundGraphic(CompoundShape cg);

}

visitor/XMLExportVisitor.java: Concrete visitor, exports all shapes into XML

package algamza.visitor.example.visitor;

import algamza.visitor.example.shapes.*;

public class XMLExportVisitor implements Visitor {

public String export(Shape... args) {

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder();

for (Shape shape : args) {

sb.append("<?xml version=\"1.0\" encoding=\"utf-8\"?>" + "\n");

sb.append(shape.accept(this)).append("\n");

System.out.println(sb.toString());

sb.setLength(0);

}

return sb.toString();

}

public String visitDot(Dot d) {

return "<dot>" + "\n" +

" <id>" + d.getId() + "</id>" + "\n" +

" <x>" + d.getX() + "</x>" + "\n" +

" <y>" + d.getY() + "</y>" + "\n" +

"</dot>";

}

public String visitCircle(Circle c) {

return "<circle>" + "\n" +

" <id>" + c.getId() + "</id>" + "\n" +

" <x>" + c.getX() + "</x>" + "\n" +

" <y>" + c.getY() + "</y>" + "\n" +

" <radius>" + c.getRadius() + "</radius>" + "\n" +

"</circle>";

}

public String visitRectangle(Rectangle r) {

return "<rectangle>" + "\n" +

" <id>" + r.getId() + "</id>" + "\n" +

" <x>" + r.getX() + "</x>" + "\n" +

" <y>" + r.getY() + "</y>" + "\n" +

" <width>" + r.getWidth() + "</width>" + "\n" +

" <height>" + r.getHeight() + "</height>" + "\n" +

"</rectangle>";

}

public String visitCompoundGraphic(CompoundShape cg) {

return "<compound_graphic>" + "\n" +

" <id>" + cg.getId() + "</id>" + "\n" +

_visitCompoundGraphic(cg) +

"</compound_graphic>";

}

private String _visitCompoundGraphic(CompoundShape cg) {

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder();

for (Shape shape : cg.children) {

String obj = shape.accept(this);

// Proper indentation for sub-objects.

obj = " " + obj.replace("\n", "\n ") + "\n";

sb.append(obj);

}

return sb.toString();

}

}

Demo.java: Client code

package algamza.visitor.example;

import algamza.visitor.example.shapes.*;

import algamza.visitor.example.visitor.XMLExportVisitor;

public class Demo {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Dot dot = new Dot(1, 10, 55);

Circle circle = new Circle(2, 23, 15, 10);

Rectangle rectangle = new Rectangle(3, 10, 17, 20, 30);

CompoundShape compoundShape = new CompoundShape(4);

compoundShape.add(dot);

compoundShape.add(circle);

compoundShape.add(rectangle);

CompoundShape c = new CompoundShape(5);

c.add(dot);

compoundShape.add(c);

export(circle, compoundShape);

}

private static void export(Shape... shapes) {

XMLExportVisitor exportVisitor = new XMLExportVisitor();

System.out.println(exportVisitor.export(shapes));

}

}

OutputDemo.txt: Execution result

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<circle>

<id>2</id>

<x>23</x>

<y>15</y>

<radius>10</radius>

</circle>

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<compound_graphic>

<id>4</id>

<dot>

<id>1</id>

<x>10</x>

<y>55</y>

</dot>

<circle>

<id>2</id>

<x>23</x>

<y>15</y>

<radius>10</radius>

</circle>

<rectangle>

<id>3</id>

<x>10</x>

<y>17</y>

<width>20</width>

<height>30</height>

</rectangle>

<compound_graphic>

<id>5</id>

<dot>

<id>1</id>

<x>10</x>

<y>55</y>

</dot>

</compound_graphic>

</compound_graphic>